As Osiris lives, he also will live; as Osiris dies not, he will not die….

—The Pyramid Texts (ancient Egypt)

…And sins forgeuenesse.

And of the flesh the again-rising…

—The Apostles’ Creed (pre-Norman England)

Osiris Rising

The Egyptian understanding of resurrection is wrapped up with the story of Osiris. Osiris, the myths say, was the first king of Egypt and a son of Ra. He was husband and brother to Isis, who first discovered grain. Osiris taught men religion, agriculture, and the arts of making wine and brewing beer. As a result of all this, he was worshipped as a god. His wicked brother Set envied his popularity and so, with seventy-two conspirators, plotted Osiris’s death. Surreptitiously, Set obtained his brother’s measurements. Then he built a beautiful coffin-like chest to match those specifications. He threw a party, supposedly to celebrate his brother’s reign, and included his co-conspirators. In the midst of the festivities, Set revealed the chest. Lightly, he offered it to whomever it might fit best. One by one, the conspirators lay down in it, but they were all too short or tall or wide. Finally, Osiris lay down inside the chest. Of course, it fit perfectly. The conspirators immediately rushed to the chest, slammed down its lid, and sealed it over with molten lead. Then they threw the chest into the Nile, confident that their enemy was dead. The chest, now a working coffin, drifted out to sea and north along the coast.

The grieving Isis went in search of the coffin. She found it at Byblos and, with the help of the local king and queen, was able to bring it back to Egypt. Set got a hold of it, however, while Isis was away. He broke it open and tore Osiris’s corpse into fourteen pieces. These he scattered up and down the Nile. When Isis returned, she set out yet again to find her husband’s dismembered body. In a papyrus boat, she sailed up and down the Nile, collecting the pieces. She found all but one. That one she replaced with a gold replica. (This is the mythological basis for phallus worship in Egypt.) With the help of her son Horus, the god of words and spells, Isis was able to bandage the pieces of the body back together and breathe life back into her husband’s corpse. Osiris returned to life, but to a life beyond the grave, a life in the Underworld. From there he would reign as lord and god, presiding over the judgment of those who pass out of this life. His fate became the inspiration and pattern for the Egyptian approach to death.

Egyptian Burial

We know, of course, of the massive pyramids and the royal tombs carefully sequestered in the Valley of the Kings. These were designed to protect the mummified remains of the departed pharaohs till the end of time. Egyptians attached the greatest importance to the preservation of the body after death. “They cleansed it and embalmed it with drugs, spices and balsams; they anointed it with aromatic oils and preservative fluids; they swathed it in hundreds of yards of linen bandages; and then they sealed it up in a coffin or sarcophagus, which they laid in a chamber hewn in the bowels of the mountain. All these things were done to protect the physical body against damp, dry rot and decay, and against the attacks of moth, beetles, worms and wild animals” (E. W. Budge, The Book of the Dead, xi). They believed the spiritual nature of man was tied to his material body. For the one to enjoy eternal life, his body had to be preserved in this world. And not only preserved, but provided for. The Egyptians, both noble and commoner, were buried with foodstuffs, utensils, clothes, and jewelry—everything that would make for a happy eternity in the world to come. (Eventually, magically enhanced images of these were accepted as valid substitutes.) Where possible or economically viable, the deceased’s descendants were charged and bound to provide sacrificial food for the immortalized soul of their ancestor.

Resurrection through Magic

The Egyptians believed in a resurrection through death into another world, another dimension of existence. They did not believe that the body in the tomb would ever come back to life in this world. They believed that it had to be preserved so that its spiritual essence could continue its existence in the next world.

Now the Egyptians certainly understood that there must be some ethical requirement for entry into life eternal. And so in their deaths, they protested their righteousness:

But usually the protestation was of a negative sort:

I have not blasphemed a god,

I have not robbed the poor.

I have not done what the god abhors,

I have not maligned a servant to his master.

I have not caused pain,

I have not caused tears.

I have not killed….

But this “Negative Confession,” as the archaeologists call it, falls within the spells of the Book of the Dead. It is an incantation to deceive or compel the gods into accepting the dead man as righteous. For the Egyptians, magic trumped ethics. The salvation found in Osiris was the work of magic performed through repetitive chants and esoteric words and rites. If the priests or the family of the deceased did to his body what Isis had done to that of Osiris, the dead would live as Osiris did. Indeed, he would become like Osiris. He would become god.

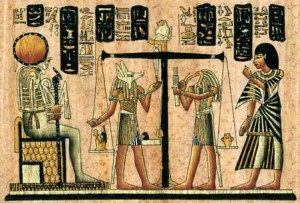

By the time of the New Kingdom, the Egyptians believed that every human soul that had been properly prepared and magically armed would make its way from its tomb past the lurking demons and serpents and stand before Osiris. There the jackal-headed Anubis would weigh its heart against the feather of truth. Those who passed this judgment would go on to eternal life as gods; those who failed, whose hearts outweighed the feather, would be consumed by the crocodile-headed Devourer of Souls. But the spells in the Book of the Dead guaranteed that wouldn’t happen. They were a magical insurance policy that bound even the gods.

If a Man Die, Shall He Live Again?

Like the Egyptians, the ancient Hebrews carefully preserved and adorned the bodies of their dead. (See Gen. 23, for example.) They often went to great expense to prepare a body for burial. And it was always burial, never cremation. The Hebrews respected the body, even in death, because they believed in its future resurrection out of death. So the patriarch Job could say:

For I know that my redeemer liveth, and that he shall stand at the latter day upon the earth: and though after my skin worms destroy this body, yet in my flesh shall I see God: whom I shall see for myself, and mine eyes shall behold, and not another; though my reins be consumed within me. (Job 19:25-27)

The New Testament Church shared this faith. After all, it was founded on the bodily (fleshly) resurrection of Jesus Himself. In fact, Paul writes that the resurrection of Christ and that of believers are bound up together in the gospel message:

Now if Christ be preached that he rose from the dead, how say some among you that there is no resurrection of the dead? But if there be no resurrection of the dead, then is Christ not risen: and if Christ be not risen, then is our preaching vain, and your faith is also vain. (1 Cor. 15:12-14)

No resurrection of the dead, no resurrection of Christ and no redemption from sin. Or, put the other way around, “For as in Adam all die, even so in Christ shall all be made alive.” (1 Cor. 15:22) Death is the fruit of sin; it is God’s judgment on man’s disobedience (Gen. 3). And so Yahweh’s final triumph over sin has to mean the end of death as well. For the Christian, redemption from sin and the resurrection of the body are necessary corollaries. And basic to both is the judicial forgiveness of sins through Christ’s substitutionary death. Christ bore the curse of death on the cross so that we might have resurrection life at His return. That life will be one of joy and righteousness in the renewed creation (2 Pet. 3:13).

Conclusion: “Resurrection” and Resurrection

Egyptian religion aims at the deification of man through myth and magic. Christianity is concerned with the ethical relationship that exists between the finite creature and his sovereign Creator. The Egyptian “resurrection” offers men an escape from this world and deification in the next: it offers escape from creaturehood. The biblical doctrine of the resurrection confirms men in their creaturehood, but it also promises Christians eternal fellowship with their Creator through the forgiveness of sin. It also promises them final and complete ethical conformity to the image of Jesus Christ in the world to come. It promises the rising again of their flesh. To the humble, this is good news indeed.