I want to make a few important points before we begin, lest I be accused of systematic racism, which I detest. The Bible says there are two main types of people in the world: Creator worshipers and creature worshippers. There are other distinctions, to be sure, but it’s this principial separation that should guide us. The Bible says nothing of dividing mankind by levels of melanin in the skin.

Onward.

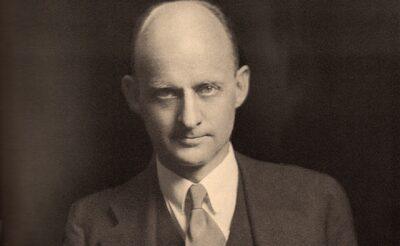

Martin Luther King Jr.’s journey into the world of theology began long before he stepped onto the big stage as a civil rights leader. Raised in a family of ministers, King inherited a spiritual outlook shaped by a biblical view of scripture and black church tradition.

It was at Morehouse College that his theology changed drastically. Enrolling at the age of fifteen, King immersed himself in liberal sociology under the guidance of progressive African American theologians and thinkers.

Figures such as Benjamin Mays and George Kelsey encouraged him to view faith as more than personal piety, challenging him to see it as an engine for their version of social justice.

At Morehouse, King was instilled with the importance of intellectual thought. Mays, the college’s president, was a towering figure who championed social justice. He once told King that an unexamined faith was hardly worth holding.

Through lectures, conversations, and campus life, King discovered that his religious commitments could not be divorced from a broader struggle for justice in the world around him. This environment propelled him toward a future ministry that was not restricted to the pulpit but extended well into the social fabric of society.

Embracing Liberal Theology at Crozer

King left Atlanta to attend Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, where he encountered neo-orthodox theological perspectives that further expanded his worldview. King felt like he found a setting conducive to critical thought and open dialogue at Crozer.

Here, he first encountered the ideas of liberal theologians like Reinhold Niebuhr and Harry Emerson Fosdick, whose works advocated a worldview that engaged with real-world problems.

These thinkers challenged King to grapple more nuancedly with sin, redemption, and moral obligation concepts. Niebuhr’s emphasis on the complexity of evil and the limits of human goodness influenced King’s belief in the need for societal transformation. Fosdick’s approach underscored the importance of “progressive” Christianity, urging believers to commit themselves to social reform and empathetic action.

Rather than seeing religious life as confined to confessional belief, King came to view theology as a lens through which the struggles of everyday life could be interpreted and addressed. The seeds planted at Morehouse were thus nurtured at Crozer, enabling King to refine his theological framework and strengthen his commitment to his beliefs regarding social justice.

Doctoral Pursuits at Boston University

After completing his Bachelor of Divinity at Crozer, King pursued doctoral studies in systematic theology at Boston University’s School of Theology. Boston was fertile ground for a curious mind like King’s, offering a vibrant academic community that introduced him to Paul Tillich, Rudolf Bultmann, and Edgar Brightman.

Tillich’s existential theology, emphasizing the “ground of being,” helped King explore a conception of God that transcended biblical moral codes. Bultmann’s approach to demythologizing Jesus and the New Testament urged King to reconcile ancient religious texts with modern-liberal interpretations. Brightman’s personalism, a philosophy highlighting each individual’s moral significance and worth apart from the bible, dovetailed neatly with King’s inclinations toward human dignity exemplified by Gandi.

While some academic effort defined King’s time in Boston, he was also involved in local churches, applying his classroom insights in pastoral contexts. In these settings, King began honing the oratory skills that would later echo across the nation. The seeds of his powerful preaching style took root in these humble chapels, where he led services and engaged congregations with his beleifs.

While King plagiarized much of his doctoral work, his time in Boston refined his intellect and capacity, allowing him to share his neo-orthodox theological ideas in accessible and inspiring ways.

The Eager Student of Books

Alongside his formal education, King cultivated a voracious appetite for reading. From early adulthood onward, he devoured works of philosophy, social theory, and theology. Karl Barth’s neo-orthodox perspective, emphasizing the sovereignty of God and the centrality of Christ, left a lasting impact.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s writings on costly discipleship and the responsibility of Christians to oppose injustice resonated with King’s growing conviction that faith must be lived out in concrete actions. Reinhold Niebuhr reappeared in King’s reading, reinforcing that an active engagement with societal ills was intrinsic to even humanistic Christianity.

Reading was, for King, an act of integration. He synthesized ideas from liberal theologians and secular philosophical treatises to forge an intellectually grounded yet pastorally sensitive theology. Though his theology evolved as he encountered fresh challenges, a guiding principle remained consistent… faith… even when directed from scripture, could be both personal and communal, calling individuals to transform themselves and their societies.

Core Theological Convictions

King’s theology, woven from these academic and personal threads, placed an abstract “justice” at the center of his Christian message. This theology was not merely sentimental or passive but an active force capable of confronting systems of oppression.

King believed that the divine presence calls humanity to unity and reconciliation and that each person bears the image of God. This conviction anchored his advocacy for nonviolence as not merely a tactical approach but a profound theological statement about the nature of God and humanity.

He also wrestled with the tension between the brokenness of the human condition and the hope offered by redemption. Influenced by Niebuhr’s realism, King recognized that evil could not be ignored or wished away. Yet, following Bonhoeffer and Brightman, he asserted that the faithful must act against injustice, rooted in the conviction that moral courage reflects God’s will for the world. King’s life and ministry thus became an ongoing effort to live out these convictions with both heart and mind engaged.

Continuing Legacy of Faith

Though often remembered as a civil rights leader, Martin Luther King Jr. was first and foremost a “modernist” theologian who believed that God’s call to love extends into every corner of human existence. His education at Morehouse, Crozer, and Boston University served as the scaffolding upon which he built a theology that balanced critical inquiry with faith.

This theological foundation significantly influenced his approach to civil rights leadership, shaping his belief in the transformative power of action. Mentors like Benjamin Mays and George Kelsey lit the initial spark. At the same time, theologians such as Tillich and Barth fanned the flame of his expanding neo-orthodox worldview. The books he devoured and the classrooms he inhabited played their part in shaping a man whose convictions about justice, redemption, and human dignity still resonate today.

King’s theological legacy endures because it remains anchored in his quest for justice. His faith, informed by modernist intellectuals and enriched by pastoral practice, was not a separate entity from his civil rights work, but rather the guiding force behind it.

King’s FBI Files Have Been Sealed Since 1977

We may find out more about Martin Luther King’s ability to “walk the theological talk” in 2027 as his sealed FBI files, which have been sealed for 50 years, will be unsealed.

The court order to seal Martin Luther King’s FBI files was initiated by Coretta Scott King, Martin Luther King’s wife, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). In 1977, they filed a lawsuit against the FBI and the Department of Justice to prevent the release of King’s FBI files, which contained sensitive and potentially embarrassing information about his personal life.

The lawsuit was prompted by concerns that the FBI had engaged in a campaign of surveillance and harassment against King during his lifetime, and that the release of the files could damage his reputation and harm his family. As part of the settlement agreement, a federal judge ordered that the files be sealed for 50 years.

It’s worth noting that some sources suggest that Senator Ted Kennedy also played a role in advocating for the sealing of King’s FBI files. Kennedy was reportedly concerned about potential embarrassment to prominent politicians and civil rights leaders who may have been mentioned in the files.

Regardless, King’s work in the Civil Rights Movement needs to be acknowledged. But here’s the thing: we aren’t honoring Dr. King by championing him as a simple bible believing Christian. He was not. He said as much. Telling the truth about him might take some courage, but my guess is that he would like to be known for the theology he loved, even if much of it was modernist and Neo-orthodox.