Man’s ability to harvest the earth’s immense bounty has been the key to human prosperity and societal development over the past several thousand years. Even when once-mighty empires have crumbled and formerly dominant cultures and peoples have fallen into obscurity, new societies have always risen from the ashes to achieve unique and remarkable things. Unquestionably, this pattern of irrepressible accomplishment has its foundation in the ability of human beings to come up with increasingly more clever and inventive ways of efficiently capturing and using the limitless resources that creation so generously provides.

Man’s ability to harvest the earth’s immense bounty has been the key to human prosperity and societal development over the past several thousand years. Even when once-mighty empires have crumbled and formerly dominant cultures and peoples have fallen into obscurity, new societies have always risen from the ashes to achieve unique and remarkable things. Unquestionably, this pattern of irrepressible accomplishment has its foundation in the ability of human beings to come up with increasingly more clever and inventive ways of efficiently capturing and using the limitless resources that creation so generously provides.

In the past, much propaganda was generated in praise of man’s supposed ability to “conquer” nature through science and technology. But this sort of metaphor has now gone out of fashion, as thoughtful people have come to recognize that our species’ incredible record of success is based more on our ability to work with the forces of nature rather than against them. Cooperation, not exploitation, has fueled the furnaces of human achievement, and when formerly great societies have forgotten this truth, they have inevitably lost their innovative edge and begun a long gradual descent into extinction.

We are now nearing the end of another era where human hubris has eclipsed common sense, and with collapse seemingly just around the corner, the search for alternative ways of living has taken on a renewed sense of urgency. Finding methods to harvest the earth’s resources more consistently, efficiently, sustainably, and affordably will be the key factors that will drive the next renaissance, and those who have dedicated themselves to living off-the-grid are helping to set an example as to how things can and should be done as we move inexorably forward into an uncertain future.

In their quest to find the best and most practical technologies, some off-the-gridders have turned to air-source heat pumps for indoor climate control. This type of heat pump works by extracting the warmth that all air contains and relocating it to a more appropriate location for the purposes of heating or cooling. While these devices work quite effectively, however, requiring only a small input of electricity to produce impressive amounts of natural indoor temperature moderation, they are not the only heat pump option available in the marketplace.

While the air can conceivably supply free warmth perpetually, the ground beneath our feet is capable of replicating this feat with even more ease. Geothermal heat pumps can be used to liberate the heat stored in the earth and to transfer it to our homes in the wintertime at a rate of efficiency that even the most state-of-the-art air-source heat pumps cannot hope to approach. Or, conversely, these technological wonders can remove excess heat from the home during the dog days of summer and pump it directly into the ground, where it will then be effortlessly absorbed and dispersed.

Geothermal Heat Pumps: The X-Y-Zs

No matter how hot or cold it may be on the surface, if you go six feet straight down into the earth, you will discover an entirely different state of affairs. At this depth, temperatures generally stay in the 45-to-75-degrees Fahrenheit range throughout the year, and when the mercury rises above or drops below this level, the earth can be used with a high degree of efficiency as either a heat source or a heat sink – but only if your homestead has been supplied with a well-constructed geothermal heat pump system.

The technology behind these units has been around since the 1940s, and it is a little surprising that geothermal heat pumps are not more well-known or widely used, given the fact that they are at least twice as efficient as air-source heat pumps and can lower average annual home energy consumption by 30-40 percent. Geothermal heat transfer systems carry a hefty price tag, usually costing anywhere from $2,000 to $4,000 to install, but they can save the equivalent of between $300 and $1,000 on electricity or fuel each and every year, meaning that a geothermal heat pump will normally pay for itself in about five to ten years.

Presently, about 50,000 new geothermal heat pump systems are being installed in the U.S. each year, and 95 percent of those who have been using this technology to heat and/or air condition their homes say they would recommend these ingenuous devices to their friends and family. The lifespan of a geothermal heat pump is generally about twenty-five years, and the part of the system that extends into the ground can last for as long as fifty years or more before it will need to be replaced.

The Ultimate Guide To Self-Sufficient Living For Country, Urban, and Suburban Folks

How They Work

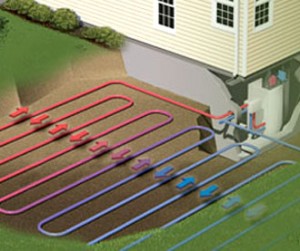

Like all heat pumps, geothermal units rely on a refrigerant that can be continuously converted from liquid to gaseous form and back again by a compressor, allowing this chemical to either absorb or shed heat as it transforms from one state to the other. In some set-ups, the refrigerant will be pressurized and circulated through a long, twisting, looped arrangement of copper piping that passes from the house down into the earth to levels of four to six feet or more, transporting the heat it collects underground back up into the house— or vice versa when the heat pump has been switched to cooling mode. In other systems, a closed loop made of plastic tubing will circulate water or an antifreeze solution down into the earth and back again, after which a heat exchanger will be used to transfer the warmth picked up below the earth’s surface into a separate refrigerant solution, which is circulated and alternately pressurized or de-pressurized by a compressor inside the home (or, if the home is being cooled instead of heated, the heat will pass from refrigerant to heat exchanger to underground loop). In still another variant, the coiled piping arrangement will actually be left open to a well or accessible source of ground water, and a continuous through-flow of fresh liquid solution will be used to carry heat either up from or down into the earth.

While most geothermal heat pumps work by transferring heat from beneath the ground to the surface, temperature differentials also allow functioning units to be installed beneath water. In a pond/lake system, the coiled loop of pipe that carries the heat-absorbing medium will first pass from the house down into the ground, but will eventually emerge from the earth several fee under the surface of an adjacent body of water, where temperatures tend to resist the extremes experienced above ground. The one stipulation is that any pond or lake used in a water geothermal set-up must be at least ten feet deep, so the pipes will be submerged deeply enough not to freeze up during the winter.

As is the case with air-source heat pumps, geothermal units terminate with a fan that is located inside the wall of the home. This fan will draw in and redirect all of the heat released by the refrigerant, distributing it to the various rooms of the house through a traditional ductwork-and-vent system. And of course, with a simple flip of a switch, the air and heat flow can be reversed during the months when an air conditioning effect is desired.

Both geothermal and air-source heat pumps require an electrical input to make the systems function. However, geothermal units have a great efficiency advantage, thanks to the smaller fluctuations in temperature that occur beneath the ground in comparison to the air (the hotter or colder it gets in summer or winter, the harder an air-source unit will have to work to remove and/or relocate the heat it extracts). Additionally, geothermal heat pumps are quieter than air-source pumps, last up to ten years longer on average, and require much less maintenance. Some units even come with two-speed compressors and variable fans to increase their efficiency and functionality even further. Because variations at the surface level do not affect temperatures below ground beyond a depth of just a few feet, geothermal heat pumps are able to continue supplying heat even during the coldest winter days, when air-source units can no longer function effectively and must be shut down.

Adding to their utility and versatility even further, some geothermal heat pumps are outfitted with a handy device called a desuperheater. These add-ons can divert a portion of the heat that is collected by the heat pump for the purposes of heating water, and they can cut down on water heating costs by as much as one-half in the winter time.

For A Better Future…And A Cheaper One, Too

Those who have installed geothermal heat pumps in their homes may still need to rely on a back-up heating system when it gets really cold. However, they will not have to rely on it completely during frigid weather the way air-source heat pump owners must. Many are choosing air-source units because the up-front costs are less daunting, but there is no doubt that in the long run geothermal systems offer bigger energy savings, fewer hassles, and more dependable performance.

For off-the-gridders living on a budget (which means virtually all, obviously), geothermal heat pumps may seem like one of those extravagant extras that they cannot afford to include in their plans. But shortsighted thinking is precisely why our society is now edging toward the cliff that overlooks the canyon of collapse and disaster, and those who are determined to pursue a more intelligent alternative should not be too quick to bypass good opportunities to live more efficiently when they come along. At the core, geothermal heat pumps are simplicity in action, but they represent exactly the sort of technological innovation that will help us re-establish a relationship with nature and all of God’s creation that can continue to be productive and sustainable even as ephemeral cultures and political orders fade from existence.