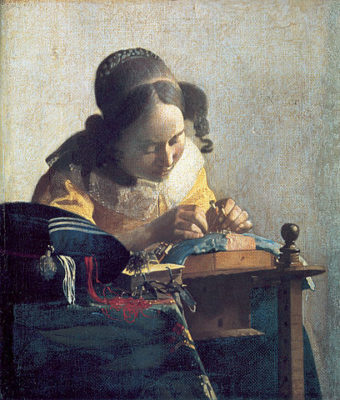

Years ago, my husband, then a young art student, visited Belgium. There, he was delighted to meet an old woman, bobbins spread out on a pillow in front of her, making lace. The woman, of course, reminded him of one of his favorite paintings, “The Lacemaker” painted by Johann Vermeer around 1670. He was happy to know that the ancient art of bobbin lacemaking was still alive and well, if practiced only by a few. Although lacemaking machines have largely replaced handmade lace, Belgian lacemaking remains a mysterious and highly sought-after art.

The History of Belgian Lace

Experts have discovered bobbins made of bone at ancient Roman sites, leading them to speculate that the ancient Romans may have made lace. However, the first known lacemakers came from Italy and Belgium in the fifteenth century. The earliest forms of lace were probably produced by nuns in convents and used to decorate religious clothing or altars.

Prior to this time, seamstresses embellished clothing with embroidery or a lace-like material developed by removing threads from a woven cloth to produce a pattern. True lacemaking is created by adding rather than removing threads and falls into two general categories.

Needle lace is created by drawing a pattern on a heavy backing. The seamstress uses a needle and thread to fill in the pattern. After the pattern is complete, the backing is removed. Bobbin lace is a much more complicated affair, created by twisting threads attached to bobbins over a network of pins attached to a pillow. Once the lace is complete, the pins are removed. Bobbin lace is the type of lace one typically thinks of when referring to Belgian lace.

Bobbin lace quickly gained popularity in Belgium and the Netherlands. In the late 1500s, King Charles the Fifth decreed that lacemaking should be taught in all schools and convents in Belgium provinces. Soon, orphanages funded by the Catholic Church taught lacemaking as a means of providing young girls a skill to support themselves. Girls in most households learned to make lace, which allowed them to save money for a dowry or add to the family budget.

Lace became a highly prized commodity during the Renaissance period, embellishing everything from altar cloths to clothing. During the Elizabethan period, all but the lowest classes wore elaborate ruffs, each of which required several yards of costly lace. One of the chief attributes of lace was that it could be removed from one garment and added to another. Wealthy aristocrats wore lace as a sign of their prestige and style, and young women included lace in their dowries, along with gold and other valuables. The division of lace among family members was even included in wills, and lace was passed from generation to generation.

The manufacture of lace was a significant source of income and growth during this period, and whole communities were built up around its production. Anthropologists believe that the lacemaking industry was one of the earliest means for a measure of independence for women.

This new DVD set is filled old world skills needed for your family…

As styles changed, the demand for lace decreased. Queen Victoria gave lacemaking a boost when she chose a white wedding dress over the traditional royal silver one. She wanted a white dress specifically so she could adorn it with lace. Thanks to her, the tradition of a white dress and veil trimmed with lace was born and remains popular to this day.

By the early 1800s, inventors had developed machines to make lace. This invention cost millions of lacemakers their jobs, and an entire industry collapsed overnight. Fortunately, the tradition of Belgian lacemaking continues to this day for several reasons. First, lacemakers specializing in bobbin lacemaking were taught only one particular skill. Several women worked together on one piece of lace, each performing a specialized task. The pieces were then put together to make one piece of lace. Therefore, the entire process of bobbin lacemaking remained a secret, not to be duplicated by machinery.

Bobbin Lace Technique

Bobbins, of course, are the distinguishing characteristic of the Belgian lace technique. Historically, they were carved from wood or sometimes fish bones and served three purposes: they stored the thread to keep it organized, they served as handles to move the thread, and they kept the thread taut across the pillow. Pins, also made from wood or fish bones, outlined a pattern on a stiff pillow. Lacemakers typically used linen or silk thread or, more rarely, human hair to make lace.

Like the “purl” and “knit” stitches basic to knitting, bobbin lacemaking relies on only two main movements, the “cross” and “twist.” Slight variations existed across geographic regions, of course, but the basic bobbin lacemaking techniques have remained largely unaltered for centuries.

If you’re interested in learning bobbin lacemaking, your best bet is to find a class. Start by contacting a bobbin lacemaking guild or organization, such as the Lace Guild (www.laceguild.com). Visit https://www.arachne.com/guild/country.cgi?USA for detailed listings of lace guilds throughout the U.S. Several experts have written helpful books as well. Bobbin Lacemaking by Doris Southard is a classic text, and Southard is considered one of the foremost authorities on lacemaking. Another good resource to try is Beginner’s Guide to Bobbin Lace by Gilian Dye and Adrienne Thunder.

Another challenge you may have initially is finding bobbins and supplies, since most craft stores don’t sell these. Try online vendors, such as Mielke’s Fiber Arts (www.mielkesfarm.com) or lacemaking.com, which offers wholesale discounts.

Bobbin lacemaking is a fine old art worth learning. Belgian lace has a delicate, open pattern that perfectly complements bed skirts, fine linens, christening gowns, and wedding dresses. Take up this enjoyable, addictive craft, and you might even find yourself with a newfound source of income since handmade lace still commands a pretty penny.

©2012 Off the Grid News