White blood cells are our body’s guards, always looking for harmful germs or infected cells. In recent years, scientists have learned how to build tiny copies of these cells in the lab, hoping to use them for new treatments.

These “synthetic white blood cells” could fight disease, deliver medicine directly where needed, and even help in cancer therapy. They could also be designed as bio-weapons, which deliver deadly toxins as part of a nano payload technology.

Here is how they work, why they matter, and what challenges they may help solve in the future.

Understanding White Blood Cells

White blood cells, also known as leukocytes, patrol the body looking for signs of trouble. They help spot invaders like viruses and bacteria and often destroy them before they cause serious harm.

Some types of white blood cells, like neutrophils, act quickly to reduce inflammation. Others, like macrophages, remove dead cells and help control infections. Still, others, like dendritic cells, create representations of germs that signal T cells so that the body can remember how to fight them in the future. Together, these cells are the cornerstone of a healthy immune system.

Despite their vital role, sometimes white blood cells can get overwhelmed by diseases such as cancer or autoimmune disorders. They can also fail to reach certain parts of the body quickly enough.

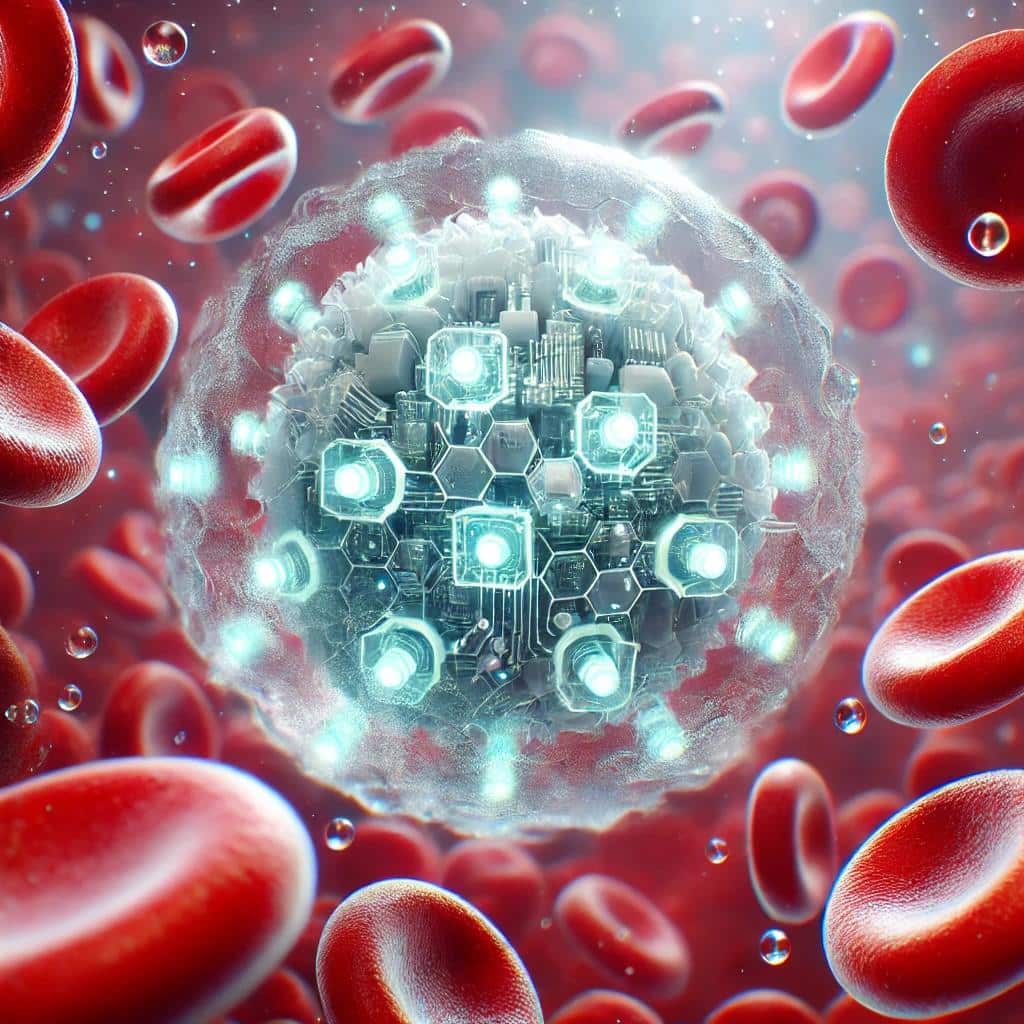

Scientists have begun designing tiny synthetic particles that behave like natural white blood cells to fix this. These particles can travel through the bloodstream without signalling an immune system’s attack. They can head straight to problem areas, such as inflamed tissues or tumors.

What Are Synthetic White Blood Cells?

Synthetic white blood cells are not living cells. Instead, they are man-made particles formed from materials like polymers or silica. Researchers then coat these particles with cell membranes taken from real white blood cells (Jiefu Jin et al., 2020).

This coating provides the particles with the same surface markers found on real leukocytes. These markers help natural white blood cells recognize the particles as “friendly,” which prevents them from being attacked and destroyed too soon.

In some studies, scientists have taken membranes from neutrophils to create nanoparticles that can quickly reach inflamed areas and deliver medicine (Zhang et al., 2018). Other teams use membranes from macrophages to help the particles slip past the body’s defenses and zero in on disease sites such as tumors (Parodi et al., 2013). There are even “artificial antigen-presenting cells,” which mimic dendritic cells to help train T cells to find and destroy cancer (Sunshine et al., 2014).

How Are They Created?

The simplest way to make a synthetic white blood cell is to take a polymer bead or another small core and cover it with a membrane from an actual white blood cell (Kroll et al., 2019). Scientists grow white blood cells in the lab or collect them from donors.

They then break open these cells to remove their membranes. After cleaning and preparing the membranes, researchers wrap them around the tiny synthetic cores. Because the core is smaller than a real cell, the coating process forms a particle that is both stable and able to carry payload drugs inside.

Some scientists are combining different cell membranes to mix and match properties. One group made magnetic beads with platelet and leukocyte membranes to snag rare cancer cells in the bloodstream (Rao et al., 2020). The end goal is to give these synthetic particles specific abilities, like homing in on inflamed tissues or binding to tumor cells.

Potential Uses in Medicine

A primary use for these synthetic white blood cells is targeted drug delivery. They can hide from the immune system and travel in the body much longer than uncoated nanoparticles (Parodi et al., 2013). This longer circulation means (theoretically) that drugs can be delivered more precisely, helping patients receive lower doses with fewer side effects.

Another significant area of application is cancer therapy. Researchers are currently testing synthetic white blood cells designed to mimic dendritic cells, which train T cells to attack cancer cells (Sunshine et al., 2020). If successful, this approach could empower T cells to become more potent and effective in targeting tumors, potentially making previously untreatable cancers more manageable. This promising research instills hope for the future of cancer treatment.

These artificial cells also hold promise in the management of chronic conditions characterized by inflammation, such as rheumatoid arthritis. Inspired by the natural swarming of neutrophils to areas of inflammation, neutrophil-inspired nanoparticles can deliver anti-inflammatory drugs directly to painful joints (Zhang et al., 2018). This targeted approach may not only halt the spread of the disease but also minimize the risk of harming healthy tissue, offering potential relief for those suffering from chronic inflammation.

Challenges and the Road Ahead

Although early studies are promising, there are still several challenges and potential risks associated with synthetic white blood cells. Making membranes for these particles can be expensive and time-consuming. Researchers must also confirm that these synthetic cells are safe over long periods. At this time, safety standards are fuzzy and long-term studies have not demonstrated the technology as safe.

Some worry about unknown side effects if the particles stay in the body too long or break down unexpectedly. For instance, there could be potential immune responses or unintended interactions with the body’s natural immune system. Another challenge is learning how to produce them in large quantities so that they can be tested in clinical trials and, one day, used widely in hospitals.

Scientists are now experimenting with reusing or creating membranes without relying on real cells. This could lower costs and speed up production. They also develop particles that can actually shape-shift or release their cargo only after sensing specific signals in the body.

If these efforts succeed, synthetic white blood cells might become a key tool for personalized medicine, offering treatments tailored to an individual’s unique immune system and disease profile.

An Uncertain Future

Synthetic white blood cells may hold enormous promise for treating conditions like cancer and autoimmune disorders, offering more targeted and gentler therapies than many current methods. This is possible.

However, as with any powerful technology, the potential for misuse cannot be entirely ruled out. Stringent safety measures, ethical oversight, and legal controls need to be firmed up and put in place to minimize these risks. While weaponization of synthetic white cells is very possible, the technical challenges, high costs, and strong regulatory frameworks make it an unlikely choice for small terrorist groups and a great choice for large governments that can use tax dollars to pay for the weaponization of white cells.

Like all technology, the choice of using synthetic white cells for good or evil remains wide open. A basic step forward would be to inform citizens of this type of nanotechnology’s ramifications and long-term safety concerns. Playing God carries a lot of responsibility, perhaps more than scientists can ever comprehend. Slowing all this down until we can understand the full implications may be the smartest choice in the short term.